Bass dispersal after weigh-ins at fishing tournaments

Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides; Figure 1) and smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu; Figure 2) are two of the most popular species of freshwater fish in North America. Both species are voracious predators and are highly prized by anglers for their fighting ability on the line. Smallmouth bass typically feed on prey beneath the surface, such as fish, crayfish, and aquatic insects. Largemouth bass will feed on anything that can fit in their mouths, including fish, invertebrates, frogs, and even ducklings, mice, and small turtles. Their aggressive behavior and heart-pounding strikes on lures make them two of the most beloved freshwater species with anglers.

Figure 1. Largemouth bass. Photo by Steve Luell.

Figure 2. Smallmouth bass. Photo by Steve Luell.

There are differences in the habitat preferences between the two species. Largemouth bass prefer slow-moving and still waters with abundant vegetation, woody debris, and sandy substrate such as lakes, ponds, and large rivers. Smallmouth bass can be found in large lakes and reservoirs as well as fast-moving rivers and streams. Unlike largemouth bass, smallmouth bass prefer clearer and cooler water with rock or gravel substrate. Because of their popularity as sport fish, both species have been stocked widely throughout the United States.

Competitive fishing tournaments have become popular in recent years. During a tournament, the bass are caught by the anglers and transported in a livewell to a designated location where the largest of the bass are weighed-in. After the weigh-in, the bass are released into the surrounding waters, usually in an area of the lake far from where they were originally caught. Thus, catch-and-release tournaments have the potential to displace fish outside of their known home ranges. Release into unfamiliar locations can cause stockpiling, where a sizable proportion of bass remain near the location they were released for a period of time before dispersing. When this happens, the bass can deplete populations of baitfish near the release site, and spread diseases to one another. A large concentration of displaced bass may also become vulnerable to capture due to heavy recreational fishing pressure after the tournament.

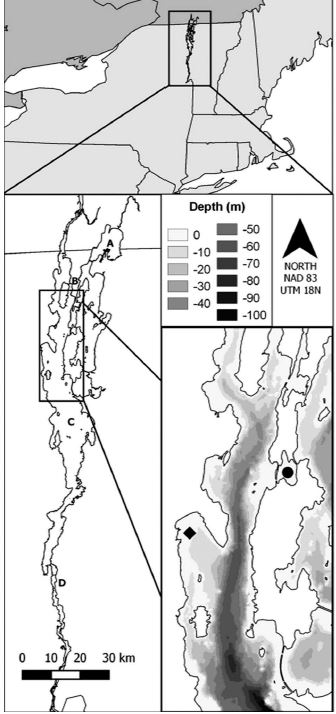

George Maynard and Dr. Tim Mihuc led a team of scientists from the State University of New York-College at Plattsburgh on a study to examine the movements and survival of bass displaced by fishing tournaments in Lake Champlain. Lake Champlain is a large freshwater lake between the Adirondack Mountains of New York and the Green Mountains of Vermont. The lake is about 193 km (120 mi) long and 19 km (12 mi) at the widest point. Though mostly situated in the United States, a small section of the lake extends into the Canadian province of Québec. Due to differences in habitat preferences, smallmouth bass were targeted by anglers in the Vermont Islands region of the lake, and largemouth bass were targeted in Missisquoi Bay on the Canadian border and in the South Lake region (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Map of Lake Champlain. The panel on the right shows the depth of the lake near the release points. The black diamond is the release point used by bass fishing tournaments in Cumberland Bay off Plattsburgh, NY. The black circle is where the reference group of bass were released at The Gut. The regions of the lake are: A. Missisquoi Bay, B. the Vermont Islands, C. Main Lake, and D. South Lake (from Maynard et al. 2017).

During the summers of 2011 and 2012, the researchers tagged 1,160 largemouth and 1,141 smallmouth bass that were caught by anglers fishing in eight major bass fishing tournaments based in Plattsburgh, New York with T-bar anchor tags. T-bar tags are long, thin tags that are anchored into the muscles and extend out of the fish’s body. They have unique alphanumeric codes on them to identify the individual fish. A subsample of those bass were also surgically implanted with radio transmitters to track their long-term movements throughout the lake. The bass captured during the tournaments were released in Cumberland Bay off Plattsburgh after the weigh-ins. A reference group of eight largemouth bass and 33 smallmouth bass that were caught at The Gut, northeast of Plattsburgh, were also tagged and released near their point of capture to monitor their movements (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A smallmouth bass with three tags. The yellow T-bar has an identification number on it, and the white T-bar identifies the fish as one that was released at The Gut. A radio antenna is visible protruding from the bass’s abdomen. Photo by Dr. George Maynard.

The radio-tagged bass were tracked weekly by boat from late April through early December. To supplement the boat tracking, aerial tracking of the radio-tagged bass was conducted by plane four times throughout the second year of the study. Recreational anglers that caught the T-bar-tagged bass during the study reported the tag number, location, and date of capture to the research team.

Over time, many of the bass left Cumberland Bay. A majority of the radio-tagged smallmouth bass (56%) quickly dispersed out of the bay. Only 43% of the largemouth bass left the bay, and they did so after staying near the release site for over two months. Due to the amount of public fishing areas along the Plattsburgh waterfront, bass that remained near the release site were vulnerable to heavy recreational fishing pressure after the tournaments. The bass from the reference group in The Gut did not disperse as far as the bass released off Plattsburgh, possibly because they were returned to a location near where they were originally captured.

The smallmouth bass dispersed farther than the largemouth bass. This may have been due to the habitat preferences of the species. Cumberland Bay is shallow with an abundance of structure, the preferred habitat for largemouth bass. Outside of the mouth of the bay, the lake is rockier, and experiences more wave action. The smallmouth bass left the bay using areas of boulders and gravelly shoal habitats along the nearshore margins of the lake to travel north or south. Both species avoided the deep (> 60 m (197 ft) deep), pelagic areas directly southwest of the release site and in the main lake, possibly because they navigate using landmarks as well as the sustained swimming effort needed to cross these areas. Only one bass, a smallmouth, returned to its approximate original capture location on the lake.

Stockpiling after the bass are released after a tournament can be problematic from a management standpoint. In smaller lakes, it could have an impact on the population structure of the bass by concentrating the larger, mature bass that are targeted by anglers. In larger lakes, it may result in permanent displacement of bass from isolated subpopulations. This research demonstrated that fisheries managers and tournament organizers should make a concerted effort to use release points that do not experience heavy fishing pressure, and are closer to the original capture location.

Reference:

Maynard, G.A., T.B. Mihuc, V.A. Sotola, D.E. Garneau, and M.H. Malchoff. 2017. Black bass dispersal patterns following catch-and-release tournaments on Lake Champlain. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 37(3): 524-535.