Invasive Asian shore crabs compete with juvenile lobsters for food and shelter

Asian shore crabs (Hemigrapsus sanguineus; Figure 1) are a small species of crab that live in rocky intertidal habitats along the coast. Native to eastern Asia and the Japanese archipelago, these crabs have inadvertently been introduced to North America and Europe, where they are considered to be an invasive species. They can tolerate a wide range of temperatures and salinities, and are highly aggressive and opportunistic omnivores. While they prefer to feed on mollusks such as mussels and snails, they will also consume small fish, crustaceans, algae and marsh grasses.

Asian shore crabs were first discovered in North America in 1988 at Townsends Inlet in southern New Jersey. Over the next decade, they rapidly spread along the East Coast and can now be found from Maine to North Carolina. Asian shore crabs are prolific spawners. Female crabs can produce three to four clutches of eggs during their spawning season (May through September), each containing about 50,000 eggs. Due to their increasing numbers and aggressive behavior, Asian shore crabs often outcompete native species for valuable resources (Figure 2).

American lobsters (Homarus americanus) support one of the most valuable commercial fisheries in the Northeastern United States and Atlantic Canada. Lobsters are especially vulnerable to predation when they are juveniles and seek refuge by sheltering in crevices or burrowing in the mud (Figure 3). Rocky intertidal zones are an important nursery habitat for juvenile lobsters (Figure 4). This can put them in direct competition with Asian shore crabs for food and shelter.

Christopher Baillie and Dr. Jonathan Grabowski from the Northeastern University Marine Science Center investigated the interspecific competition between Asian shore crabs and juvenile American lobsters. The field component of the study was conducted in the intertidal zone at Dorothy Cove in Nahant, Massachusetts. From 2013 until 2017, 1 m2 square quadrats were used to survey the fauna of the rocky habitat monthly between May and October. The quadrats were placed randomly throughout the intertidal zone and all of the crustaceans that were found within the square were counted and measured. Over the five year span, Asian shore crabs became more abundant while juvenile lobster numbers steadily declined.

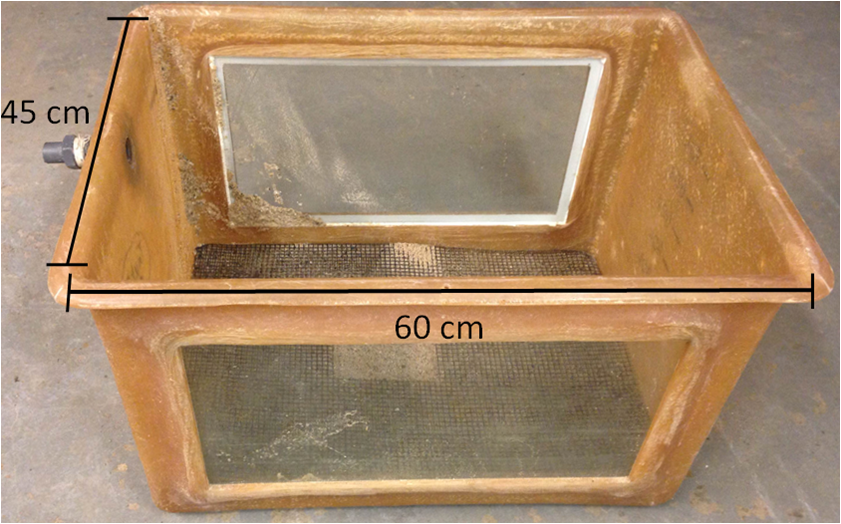

The researchers also ran three separate laboratory experiments to examine the competitive interactions between the invasive crabs and juvenile lobsters. The crabs were collected from Dorothy Cove while the lobsters were collected from the northern reaches of Casco Bay in Maine. In 2014, Asian shore crabs had not yet invaded Casco Bay so this particular population of lobsters did not have experience interacting with the crabs. For each experiment, a crab and a lobster were placed in a 100 L fiberglass aquarium with viewing windows built into the sides (Figure 5).

The first experiment examined the competitive interactions for food between the crabs and lobsters. For each trial, one crab and one lobster were selected and starved for 48 hours. They were then placed in separate opaque containers in the aquarium for one hour to become acclimated to the water. One blue mussel (Mytilus edulis), a common prey of both species, was placed in the middle. After the crab and lobster became acclimated to the tank, the containers were removed so they could roam freely around the aquarium. The lobsters likely viewed the crabs as competition and were the first to feed in all of the trials. They also fed on the mussels much faster in the presence of the crabs than if they were by themselves or with other lobsters.

The second experiment examined competition for shelter. In the center of the aquarium, a shelter was created using cinderblocks with a space inside for burrowing. Depending on the trial, a single crab or a single lobster was placed in the tank for 18 hours to become a “resident” and establish a burrow. The lobsters were generally equal to or larger in size than the crabs. Afterward, an “invader” was released into the tank. Some of the trials even pitted a lobster against multiple crabs. When there were no crabs in the tank, the lobsters generally spent their time in their burrow. Once crabs were introduced, the lobsters interacted aggressively with the crabs and defended their shelter. In several trials, the lobster even killed and ate the crab. In the trials where the crab was the resident, the lobsters were generally aggressive toward the crab.

The third experiment expanded upon the shelter experiment but used smaller lobsters that were about a half of the size of the crabs. The lobsters were the residents in this experiment and once they established a burrow, they were introduced to a variable amount of crabs. In higher densities, the crabs displayed aggressive behaviors toward the smaller lobster and drove it away from the burrow. When exposed to eight crabs, the lobster was attacked and left the burrow about 20 times on average during a span of six hours.

Interactions between species that occupy similar niches are complex. Though larger juvenile lobsters can outcompete Asian shore crabs for food and shelter, agonistic interactions have energetic costs and, in pursuing crabs outside of shelters, these lobsters may increase their vulnerability to other predators. Smaller juvenile lobsters are not as successful in competitive interactions and may be displaced from important nursery habitats when crab densities are high. In some areas in New England, the populations are so dense that more than 100 Asian shore crabs can be found per square meter. As Asian shore crabs continue expanding northward toward the Canadian border, it is important to understand how they interact with native species in the rocky intertidal zone.

Reference:

Baillie, C.J., and J.H. Grabowski. 2018. Competitive and agonistic interactions between the invasive Asian shore crab and juvenile American lobster. Ecology 99(9): 2067-2079.