The Rosgen Wars Revisited

It was the fall of 2018 and I was a graduate student in northern Minnesota. I was attending the first annual River Restoration Conference in a nearby town, and despite my relative youth in a sea of professionals, it did not take me long to pick out the conference’s keynote speaker. Beyond the white cowboy hat that bespoke a Western man in the flannel-soaked Minnesota woods, he commanded the attention of every biologist in the room. His name was Dave Rosgen.

At the cusp of my early career in fisheries, I had heard the name Rosgen but was not yet familiar enough to claim real knowledge. That would change. I soon learned that for anyone holding a conference on restoring rivers, Dave Rosgen is probably the most logical choice to figurehead it.

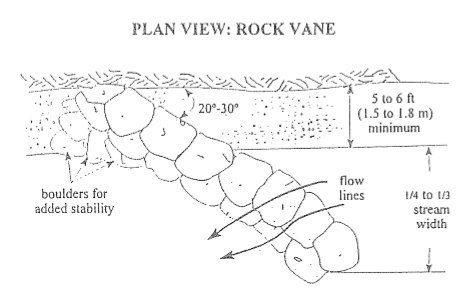

Rosgen began his career as a hydrologist with the Forest Service but rose to prominence with the advent of his flagship brainchild: Natural Channel Design (NCD), an approach for restoring impaired rivers that has since become perhaps the most popular method in the United States (Simon et al. 2007; Lave 2009). This method makes use of a classification system (also developed by Rosgen) to identify characteristics of any impaired stream and restore it to an improved state. NCD is most easily recognized by its final steps: installing rock and wood structures into the stream to adjust grade and current, reducing erosion and creating habitat features like pools. Despite little formal training in river restoration, Rosgen’s formula-based NCD approach took the lead on how to rebuild a river. In fact, many state and regulatory agencies now require training in NCD from their contractors assigned to river restoration projects. Each year, Rosgen teaches a number of classes to personnel from around the country. The entry fee alone will set you back several thousand dollars per class.

Rosgen’s approach has critics. Some professionals and academics resent the reliance and even exclusivity that has been placed on an approach with such informal origins. His step-based formula gets compared to a “cookbook” that simplifies the varied and complex group of systems that we call rivers. Ultimately, it’s undeniable that much of his strategy relies on static structures that seem to focus on solidifying rivers in place. Aren’t rivers supposed to be dynamic, changing systems? Isn’t their movement inevitable, regardless of how many rock vanes we may put on this bend or that meander?

One of the first things that early biologists learn is that ecology is not physics or math: ecology is messy. Ecology does not fit nicely into a set of categorized toolboxes on our mental shelf, to be taken down and applied perfectly to every scenario we might meet. Rosgen’s approach, however, does apply a set of standards in a field that otherwise lacks consistency, and gives some structure to a diverse group of people that work on different systems from coast to coast.

When I think back to that man in his white cowboy hat, what I remember most was his air of confidence. This was a man that knew he had critics, and knew that his approach had nevertheless still managed to float to the top of the swirling eddy that is politics in the field of ecology. Stream restoration projects need time to prove their worth, though. Over thirty years after the advent of Rosgen’s consulting group Wildland Hydrology, projects are starting to show their age. Some have been called a success (Bledsoe and Meyer 2005) and others have undoubtedly been failures (Smith and Prestegaard 2005). Time will continue to tell the value of Natural Channel Design, but for now, it retains its status as the nation’s pre-eminent method of stream restoration.

Works Cited

Bledsoe BP, Meyer JE. 2005. Monitoring of the Little Snake River and Tributaries: Year 5 Final Report. Fort Collins, Colorado: Department of Civil Engineering, Colorado State University.

Lave R. 2009. The Controversy Over Natural Channel Design: Substantive Explanations and Potential Avenues for Resolution. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 45(6):1519–1532. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2009.00385.x.

Rosgen, David L. 1996. Applied River Morphology. Pagosa Spring, Colorado: Wildland Hydrology.

Simon A, Doyle M, Kondolf M, Shields FD, Rhoads B, McPhillips M. 2007. Critical Evaluation of How the Rosgen Classification and Associated “Natural Channel Design” Methods Fail to Integrate and Quantify Fluvial Processes and Channel Response. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association. 43(5):1117–1131. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2007.00091.x.

Smith SM, Prestegaard KL. 2005. Hydraulic performance of a morphology-based stream channel design. Water Resources Research. 41(11). doi:10.1029/2004WR003926. [accessed 2020 Apr 9]. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2004WR003926.