Temperature, not tides, influence horseshoe crab spawning activity in New Hampshire’s Great Bay

The Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) is a marine invertebrate whose native range spans from the Gulf of Maine to the Gulf of Mexico. This species is ecologically and economically important. Several species of shorebirds depend on horseshoe crab eggs for food during their long distance spring migrations (Figure 1). The biomedical industry uses the horseshoe crab’s blue blood as a source for a clotting agent that aids in the detection of endotoxins in pharmaceuticals and medical devices. The conservation of horseshoe crabs depends on successful spawning events, so scientists are working to better understand the factors that influence their spawning activity.

Horseshoe crabs are well known for their unique spawning behavior. Each spring, they migrate from deeper waters into shallow estuaries and bays to spawn on intertidal beaches. Male horseshoe crabs use their pedipalps, specialized hook-like appendages, to hold on to the female’s shell. Around high tide, the female will deposit up to 4,000 eggs near the high water line as the male externally fertilizes them. Unattached “satellite” males will sometimes crowd around the pair in hope of fertilizing some of the eggs (Figure 2). After about two to four weeks, the eggs hatch and the larvae are carried into the water by the tides.

To monitor horseshoe crab populations, spawning surveys take place in many states throughout their range. Along the East Coast, the spawning season peaks in May and June. Surveys are typically scheduled during nighttime high tides coinciding with full and new moons, when the tidal ranges are at their greatest. In addition to the lunar cycle, research shows that environmental conditions also play a role in horseshoe crab spawning behavior.

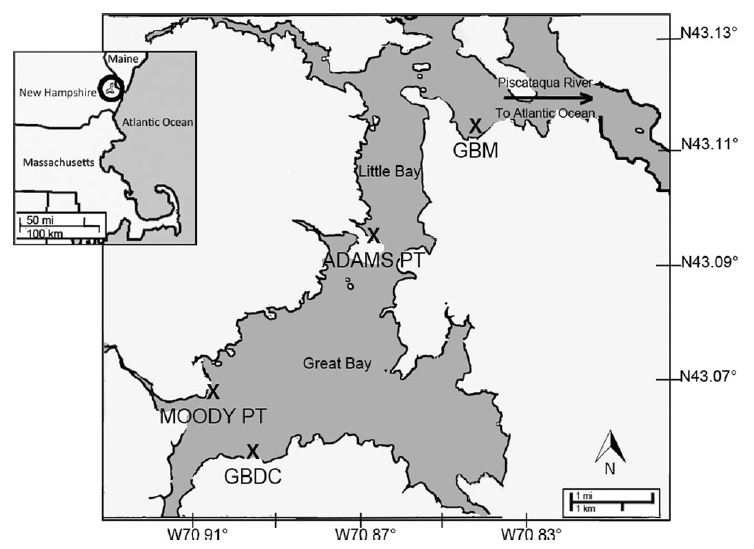

During the spawning seasons of 2012 and 2013, Helen Cheng and Dr. Win Watson from the University of New Hampshire and Dr. Chris Chabot from Plymouth State University investigated the factors that influence horseshoe crab spawning in the Great Bay Estuary in southeastern New Hampshire, including timing and spawning at greatest densities. The Great Bay Estuary is a large tidal estuary that is unique because it is located about 16 km (10 mi) inland from the coast. It is also at the northern extent of horseshoe crab’s range.

The researchers used traditional horseshoe crab survey protocols to count the spawning crabs at four locations in the estuary. At each study site, a transect was established along the beach and marked with wooden stakes. With help from volunteers, all of the horseshoe crabs along each transect (including spawning pairs, and single males and females) were counted. Environmental conditions such as water temperature and wave heights were also recorded.

The results suggest that horseshoe crab spawning activity is strongly influenced by temperature. In 2012, the water temperatures in the estuary reached 11°C (~52°F) in mid-March, about three to four weeks earlier than usual. The temperature triggered the horseshoe crabs to begin making their way toward the spawning beaches around this time. They began spawning on the beaches in early April. The following year, spawning activity began in mid May after the water temperatures warmed above 11°C. Spawning activity peaked in the estuary when water temperatures were between 15°C and 20°C. The numbers of spawning horseshoe crabs were also higher in the warmer waters of Great Bay than Little Bay (Figure 3). Wave energy was also found to influence spawning activity. Horseshoe crabs use the waves to orient themselves to the beach. Spawning was found to peak when the wave heights were moderate (<0.3m or 1 ft). The crabs generally avoided the beaches when the waves were higher due to the risk of being turned upside down and stranded.

There was no preference by the horseshoe crabs to spawn during the nighttime high tides in the Great Bay Estuary. Interestingly, many more crabs were observed spawning during daytime high tides than at night in 2012. The following year, the number of crabs spawning during the day was similar to those spawning at night. There also was not an increase in spawning activity during the high tides around new and full moons. In Great Bay Estuary, the tidal range is high regardless of moon phase. Each high tide may be “high enough” to trigger spawning. However, when there was a high tide that was higher than normal and completely submerged a spawning beach, very few horseshoe crabs were observed.

Horseshoe crab monitoring programs have traditionally scheduled spawning survey during nighttime high tides associated with full and new moons, when spawning activity was believed to peak. Water temperature appears to have an impact on the timing of horseshoe crab spawning activity in northern populations. This should be taken into account to develop more efficient protocols for assessing horseshoe crab populations.

For more information on horseshoe crab spawning surveys in New Hampshire’s Great Bay, check out Great Bay Horseshoe Crabs on Facebook.

Reference:

Cheng, H., C.C. Chabot, and W.H. Watson III. 2016. Influence of environmental factors on spawning of Atlantic horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) in the Great Bay Estuary, New Hampshire, USA. Estuaries and Coasts 39(4): 1142-1153.