Spawning sea lampreys influence macroinvertebrate communities in streams

Sea lampreys (Petromyzon marinus) are a jawless species of fish native to the northern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. They have a complex life cycle that begins and ends in freshwater. Sea lamprey eggs hatch in freshwater streams and the larvae, known as “ammocoetes”, drift downstream until they reach slow-moving waters. Once they locate a suitable habitat, they burrow into fine sediments and filter feed on algae and plankton. The ammocoetes look nothing like the adults, they are blind, and have worm-like bodies. After about four to six years, the larvae undergo a dramatic metamorphosis—they develop eyes, and a round mouth lined with sharp teeth. The young lampreys, known as “transformers”, leave their burrows and migrate to the ocean (Figure 1).

Sea lampreys are parasitic in their adult stage, using their suction cup-like mouth to attach to a host (Figure 2). Once attached, they use their rough tongue to rasp away flesh to feed on blood and other bodily fluids. The adults spend 18 months to two years feeding in the ocean before returning to freshwater to spawn. Adult sea lampreys stop feeding once they re-enter the freshwater rivers and devote all of their energy to reproduction. Their digestive systems disintegrate, their teeth fall out, and they go blind. Once they locate suitable spawning habitat, they pair up, and construct large elongated nests in the gravel stream bottom. After spawning, the adults die.

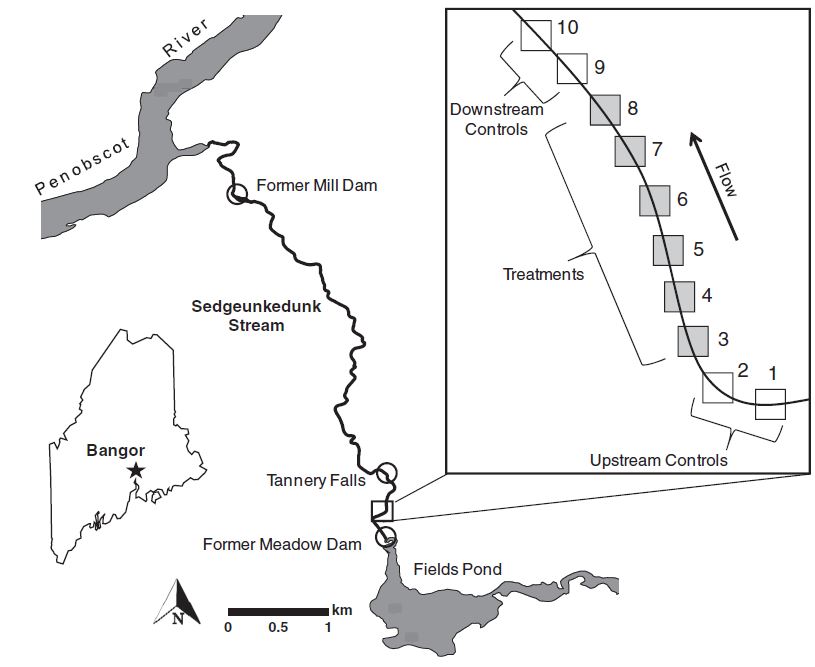

Like other anadromous fish, sea lampreys bring valuable marine-derived nutrients into freshwater ecosystems (Figure 3). The influx of nutrients can boost the productivity of other organisms in the ecosystem, such as aquatic macroinvertebrates that live on the bottom. Dr. Dan Weaver from the University of Maine led a study to examine the effects of this nutrient influx on macroinvertebrates that colonize newly constructed lamprey nests in Sedgeunkedunk Stream, a tributary of the Penobscot River in Maine.

Ten study sites were established along an experimental reach of the stream (Figure 4). Each began at a shallow area with fast moving water called a “riffle”, where swift currents carry off fine sediments and provide oxygen to the stream. The sites continued downstream into a “glide”, where the stream flows out of a deep pool, before ending at the next riffle. A mesh bag filled with clean gravel and cobble was placed at each site to mimic the cleaned and loosened substrate in a lamprey nest. Carcasses of lampreys collected from the Penobscot River were secured in metal cages at a number of the sites to decay and release nutrients into the stream. The first two sites upstream and the last two downstream were “controls”, where the researchers did not leave any carcasses. The six study sites in the middle were the “treatments”, with each receiving 20 lamprey carcasses placed about a meter upstream of the rock bag. The rock bags were examined after three weeks in the stream and were thoroughly rinsed with water to extract the macroinvertebrates that colonized them.

The results suggest that spawning sea lampreys influence the macroinvertebrate communities in streams in two ways. First, by clearing debris and fine sediment from the streambed, nesting lampreys create favorable habitats for macroinvertebrates. Spawning lampreys also shape the macroinvertebrate communities because they become a food source after they die. At the sites that received lamprey carcasses, black fly larvae were most abundant. They colonized the substrate and fed on drifting tissue that sloughed off of the carcasses. In contrast, the control sites were abundant with the larvae of non-biting midges, and net-spinning and fingernet caddisflies (Figure 5).

The timing of the sea lamprey spawning season may help to explain these results. Lampreys spawn in the spring when the water flow is typically at its highest due to precipitation and snowmelt. Under these conditions, caddisfly larvae tend to be displaced and drift downstream. Black fly larvae attach themselves to substrates, which may have favored their colonization at sites with carcasses in high flow conditions.

By adding lamprey carcasses and monitoring the bare substrate placed in the stream, the researchers were able to examine the effects spawning lampreys have on macroinvertebrates in freshwater streams. Macroinvertebrates are small and often forgotten but they play an important role in the stream ecosystem, where they are a main food source for many species of fish, amphibians and birds. They may also function as an important link in transferring nutrients from the lampreys into the freshwater food web.

References:

Weaver, D.M., S.M. Coghlan Jr., and J. Zydlewski. 2016. Sea lamprey carcasses exert local and variable food web effects in a nutrient-limited Atlantic coastal stream. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 73: 1616-1625.

Weaver, D.M., S.M. Coghlan Jr., and J. Zydlewski. 2018. Effects of sea lamprey substrate modification and carcass nutrients on macroinvertebrate assemblages in a small Atlantic coastal stream. Journal of Freshwater Ecology 33(1): 19-30.