Sea lamprey: An invasive species with a long and devastating history in the Laurentian Great Lakes

Imagine a large, suction-like mouth ringed with pointy teeth that seeks out flesh to latch onto and draw blood from. In this case, I’m not describing vampires or other fantasy creatures. I’m describing a real-life fish species: sea lamprey. This invasive species invaded the Laurentian Great Lakes in the early 1920s, and has had devastating impacts on fish populations ever since. With their elongate bodies reaching up to half a meter in the Great Lakes, and even bigger in their native range in the Atlantic Ocean, sea lamprey could be considered an apex predator in the freshwater habitats they have invaded.

Sea lamprey have a complex life cycle in the Great Lakes. They start out by hatching in streams leading to the lakes and then bury themselves in fine sediment to filter organic particles out of the water column. After about 3-5 years, they transform into parasitic juveniles that travel to the lakes to feed on large host fish. After about a year of parasitizing other fish species, they transform again, this time into adults that don’t feed. Instead, they focus their remaining energy on swimming back up streams to spawn, after which they die

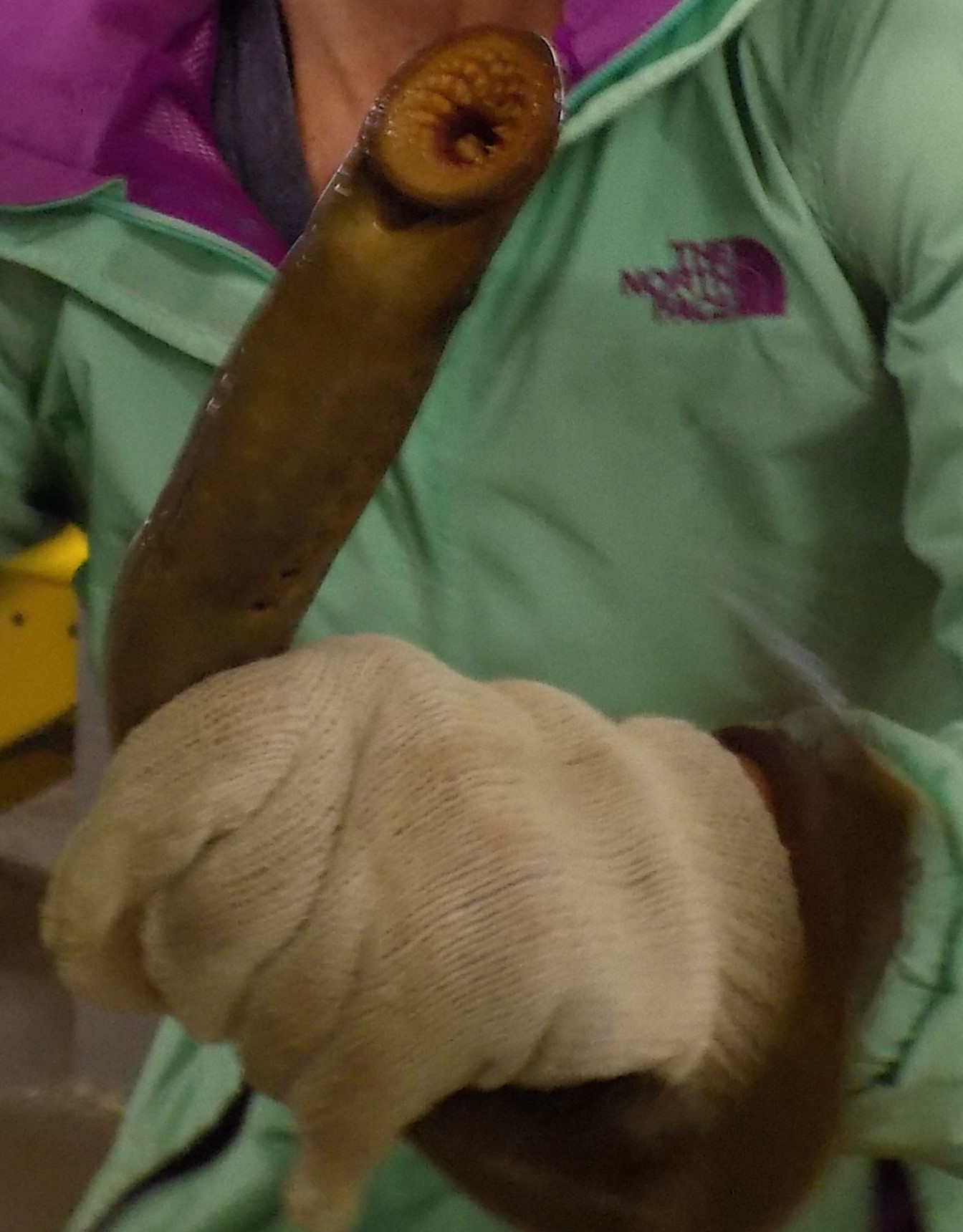

Despite their eel-like shape, lamprey aren’t eels and differ from other fish species in that they don’t have a jaw. Instead, their sucker like mouth is ringed with rows of pointed teeth—ideal for latching onto large fish species like Lake Trout that are passing by. Once attached, sea lamprey use their rasping, toothed tongue to bore a hole into the flesh of the fish they’ve latched to, and begin feeding off their host’s body fluids. This weakens and sometimes even kills their host. They feed on large Great Lakes fishes such as Lake Trout and other salmonids, Lake Whitefish, Cisco, Burbot, Walleye, and Burbot, among others.

A sea lamprey, showing the circular, suction-like mouth and elongate body. Photo credit: Adrienne McLean.

In response to sea lamprey invasion and subsequent collapses of several important Great Lakes fisheries due in-part to their parasitism, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission (GLFC) was created under the Convention on Great Lakes Fisheries (1954)—a treaty between Canada and the United States. The GLFC is responsible for sea lamprey control in the Great Lakes, and is assisted by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The GLFC currently uses three methods to control sea lamprey. The first is periodic lampricide treatment of streams and rivers that flow into the Great Lakes. These treatments target young lamprey, when they are still filter-feeding larval fish, and are very effective. The second method is the use of barriers that prevent adult sea lamprey from migrating upstream into streams that have suitable spawning habitat. The third method is trapping, which also targets adult sea lamprey that are migrating upstream to spawn, and removes them from the population before they reproduce.

A sea lamprey trap being retrieved. Photo credit: Robert McLaughlin.

These control efforts have kept the sea lamprey population at bay in the Great Lakes, reducing the impacts of sea lamprey on their fisheries and in some areas, making them appear to be a distant problem. However, sea lamprey control is an ongoing effort. Streams need to be assessed and ranked based on the amount of risk they pose in producing a high number of parasitic lamprey. Those that are at high risk get treated with the cost-limiting lampricide. Barriers in some streams keep lamprey from accessing suitable spawning habitat, but these barriers can also block the movement of desirable fish species, and so some barriers are being considered for removal, or have been removed. Trapping has had varied success, depending on the site.

Sea lamprey have been in the Great Lakes for an extended period of time, with a long history of impacts and hard-fought efforts to keep them under control. It’s therefore important to remember the impacts these invasive species had, and are continuing to have, on our native and desirable fish species in the Great Lakes.