Reemergence of North American Beaver to affect freshwater fish habitat locally and regionally

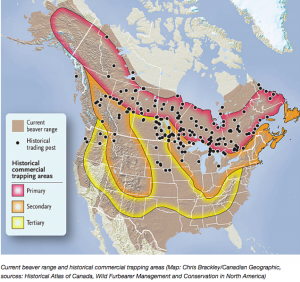

Beavers and fish, fish and beavers; these ancient aquatic associates have been sharing habitat in lakes and streams for millions of years. And yet, our understanding of how beaver engineering affects habitat quality for salmon and trout is still evolving. Two-hundred years out from the height of the North American fur trade, populations of beaver and other fur-bearing mammals are recovering in some portions of Canada and the United States, reemerging in once-treaded waters at long last. Repopulation by beaver across their native range, and even in some new areas (like Argentina), makes it an interesting time for scientists, natural resource managers, and even backyard observers to study habitat interactions between beaver (Castor canadensis) and cold-water fish, such as trout and salmon (Salmonidae).

Castor Canadensis (Source: IN.GOV)

I had the opportunity to sit down with some residents of the village of Lake Linden, MI who observed beaver frequently on their own land and the surrounding landscape. Here in the Western portion of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, an extensive forest landscape dotted by wetlands provides ample habitat and forage for beaver. There was not a consensus as to whether beaver helped or harmed salmon. Some locals described how beaver damming lead to warm stagnant pools full of fine sediments that were suitable for chub but not trout or salmon. Beavers were described by some as a particular nuisance when dams are built in culverts, flooding roads or other infrastructure and requiring repeated clearing. Some went as far to suggest a ‘seven-cent’ solution to avoid property damage, the cost of a single bullet. Other local residents rather welcomed beaver presence on the landscape. One couple recently observing dam-building activity on their creek thought the pond created by a few fallen trees and some beaver engineering created good habitat for salmon; open and deep. “We might lose a little land, but they will benefit us,” one commented, seeing the newly flooded pond as a good fishing hole.

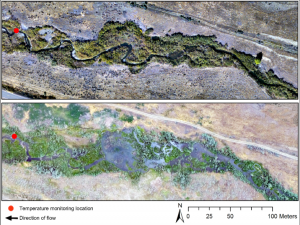

There is research to support the idea that beaver ponds can improve habitat conditions for salmon and trout. In a recently published science paper, Nicholas Weber and co-authors contradict a commonly held notion that beavers are always a detriment to fish habitat because dams disrupt stream connectivity and increase water temperatures. During high summer temperatures in a creek in Oregon, an increasing abundance of beaver dams not only supported surface water connectivity, but also kept temperatures cool when undammed portions experienced extreme water temperatures. As the number of beaver dams along Bridge Creek increased from 0 in 2007 to 9 in 2014, the wetted channel area increased by 300% and maximum daily temperatures were estimated to be 2.5o C cooler. The authors concluded that the thermal refuge provided by a high density of beaver dams will likely benefit the native steelhead trout, which rely on cool water to survive. In regions of the U.S. where Salmonid habitat is degraded and approaches thermal thresholds, a robust beaver population might be critical to fish survival and resiliency as temperatures warm.

Fig 4. Before—After beaver colonization.

Repeat aerial photography from 2005 (upper) and 2013 (lower) showing an increase in upstream pond area. (Source: Weber et al. 2017)

A similar conclusion was found by researchers on the East Coast, who measured the health condition and growth rates of 2 year old Atlantic Salmon parr in Catamaran Brook, New Brunswick, Canada. Here, buffering high summer temperature was not the greatest benefit of beaver activity, but rather an increase in open water habitat. While no significant temperature differences were found above or below dams, fish residing in beaver pools were larger and grew faster in terms of both length and width than fish below the pools. This trend was likely due to increased food availability, reduced competition, and more habitat space in the pools. Fish in beaver pools also maintained stable health throughout the summer, while the condition of those below dams declined when temperatures reached seasonal maximums.

I contacted George Madison, a Fisheries Biologist with the Lake Superior Management Unit from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to help understand this ongoing debate whether beaver dams create warm and stagnant pools unfit for salmon, or wide open pools that support health and accelerated growth. He explained that how beavers affect cold-water fish habitat could depend on geographic context. In high gradient streams with seasonal highs and lows in rainfall (and so prone to drought) such as those in Oregon, beavers may well provide thermal refuge for fish in taxing summer heat. However, in low gradient streams such as those more common to the Great Lakes basin, beavers can lead to higher temperatures, potentially unsuitable for cold-water fish. Madison shared how anglers on Presque Isle, an area that once abounded with high-quality trout streams, had been seeing far greater numbers of pike and small mouth bass. The shift from salmon to these warmer water species was blamed in part on an increasing beaver population in the area and the perception that dams increase temperatures. Madison’s unit is currently running a temperature monitoring program to hopefully learn more about regionally-specific interactions between beavers and stream temperature.

Back in Lake Linden, as we sat under a small table talking about beaver ponds, behind us hung three flags rarely displayed together, the Green Bay Packers, the Chicago Blackhawks, and Detroit Red-wings. With such a backdrop it came as no surprise that although locals disagree on whether or not beavers benefit cold-water fish, the group could find common ground on one other aspect of beaver ponds. Everyone mentioned how beaver ponds attracted a myriad of aquatic wildlife such as wood ducks, frogs, turtles, and other wetland critters. One who had chuckled earlier at the proposed, perhaps gruesome, ‘seven cent’ solution, added solemnly “they create ecosystems for all kinds of things.” Madison held had a similar perspective – while beavers were less welcomed in high quality trout streams, they were a driving force in the creation and expansion of wetland habitats, a real boon to waterfowl, amphibians, and others. He also added that beavers are a favorite food of wolf and coyote, entailing that beaver recovery might help boost those wildlife populations as well.

Back in Lake Linden, as we sat under a small table talking about beaver ponds, behind us hung three flags rarely displayed together, the Green Bay Packers, the Chicago Blackhawks, and Detroit Red-wings. With such a backdrop it came as no surprise that although locals disagree on whether or not beavers benefit cold-water fish, the group could find common ground on one other aspect of beaver ponds. Everyone mentioned how beaver ponds attracted a myriad of aquatic wildlife such as wood ducks, frogs, turtles, and other wetland critters. One who had chuckled earlier at the proposed, perhaps gruesome, ‘seven cent’ solution, added solemnly “they create ecosystems for all kinds of things.” Madison held had a similar perspective – while beavers were less welcomed in high quality trout streams, they were a driving force in the creation and expansion of wetland habitats, a real boon to waterfowl, amphibians, and others. He also added that beavers are a favorite food of wolf and coyote, entailing that beaver recovery might help boost those wildlife populations as well.

A number of scientific publications support this claim, describing how mink frogs (Lithobates septentrionalis), wood frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus), boreal chorus frogs, western toads (Pseudacris maculate and Bufo boreas), and spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) thrive in beaver ponds. Their role in supporting multiple freshwater species may be linked to the tendency of beaver dams to result in greater temperature heterogeneity, that is the creation of both warmer and cooler water niches surrounding a single dam; the beneficial effect is multiplied at the watershed scale where numerous damns can be built. Forest and natural resources management practices that support beavers may promote amphibian and reptile conservation in addition to potential fish habitat improvement on degraded streams. With current North American beaver populations estimated to number 10 to 15 million, a fraction of their historic size of 400 million or more, we are living with a shifted baseline of beaver abundance across the landscape, as well as misunderstood potential for these aquatic rodents to assist us in conserving fish habitat and wetland ecosystems.