Forestry and fish habitat linked by restoration of large woody debris in streams

Photographs by Eiko Jones

Forestry and fish habitat are interconnected across landscapes in perpetual and compelling design. Few elements of stream habitat portray this link between forest and aquatic resources as simply as fallen trees and logs seen protruding from surface waters or having come to rest in slow moving reaches. This woody debris plays an important role in river geomorphology, fish habitat, and system productivity. Whether actively transforming flows by creating pools and eddies, or simply providing shelter for freshwater animals, there is growing appreciation for the role of wood in creating and maintaining stream habitat integrity. New research aims to quantify the benefits of instream wood to aquatic fauna and describe forest management practices that might promote the production and continued deposition of large woody debris in rivers.

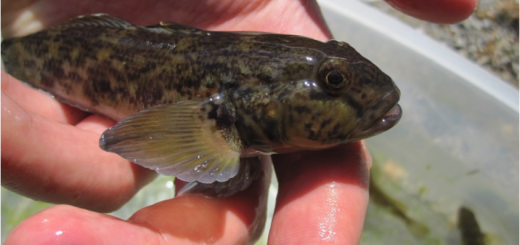

In a paper recently published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, Gonzalez et al. document that, despite divergent habitat preferences of young coho salmon and lamprey in Pacific Northwest streams, pools that feature instream wood were likely to provide quality rearing habitat to both species. Presence of large wood tended to increase surface area, allowing for greater juvenile coho abundance, and promote coverage by fine sediments, associated with presence of larval lamprey. The positive effects of large instream wood, which was classified as 3 meters or longer with a diameter greater than 15 cm, were observed whether the pool itself was formed by the large woody debris, or simply contained a piece of large wood within the habitat unit. The paper indicates that coho salmon and native lamprey species are just two of many native species of Little Wolf Creek, Oregon set to benefit from a restoration program which added 281 pieces of wood material in a series of log jams just under a decade ago.

(Large woody debris placement in Clear Creek, Oregon. Source: Clackamas River Basin Council)

In addition to the directed placement of large wood into streams for restoration purposes, a more passive approach to promoting the presence of large woody debris can be taken through land management and forestry practices that facilitate natural movements of wood into streams. Swanston described how large woody debris can be naturally deposited into streams by processes such as winds strong enough to blow down trees near streams, bank erosion that undercuts riparian trees, and mud slides, avalanches, or other mass earth movements.

Large disturbances such as fires, clear cutting, or other deforestation events, can lead to very little wood entering streams until nearby forest stands reach maturity, a process that can take decades. Much of North America’s forestlands are in a stage of secondary growth, regenerating from a legacy of lumber production for housing and firewood, shipbuilding, railway expansion, and export. The extensive logging, and in many places decimation, of old-growth forests, in addition with the historic use of streams as timber highways, greatly reduced the availability and distribution of large woody debris in rivers and streams.

Benda et al. used simulation models to determine how riparian zone management could be best directed towards generating new inputs of large woody debris into streams to make up for current-day deficits. They found that maintaining riparian buffers, and ‘tree tipping’ or the practice of felling trees directly into the water, could potentially mitigate losses of instream wood due to single entry tree harvest near streams, which can reduce the volume of dead trees from reducing competition and natural suppression. Both practices rely on streamside trees to become instream wood, as opposed to harvesting trees elsewhere for installation, and more closely mimics natural processes. Previous research found 70% or more of coarse woody debris in small streams originates from within 20m from stream banks.

Once in a river, wood can provide long-lasting benefits with residency approximated to last between 20 and 100 years. Expanding forestry objectives to include generation of instream wood is one of many ways that foresters, natural resource management agencies, and private landowners can apply land-use practices to enhance fish habitat. While maintaining sufficient riparian buffers is becoming more of an industry standard, active introduction of woody debris into streams via installations or tree tipping is becoming more popular. Partnerships between forestry and fisheries can increase the scale at which stream habitat enhancements will progress, improve accessibility to locally sourced wood materials for fish habitat restoration, and further our understanding of how to best utilize coarse woody debris resources in fisheries conservation.