Distinct life histories of Great Lakes Yellow Perch revealed in otoliths

Many animals are known for exploiting a range of habitats over the course of their life. Deer traverse forest and fen, salmon make their infamous journey between stream and sea, and some sandpipers circle the globe to take advantage of seasonally available resources. Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) in the Great Lakes are no exception and are known to exploit both coastal wetland and near shore environments. In a new study, scientists from Central Michigan University applied a new technique for tracking Yellow Perch movement between the two lake habitat niches. Tracking past movements is possible because of the assimilation of distinct earth elements unto the fish’s inner ear bone, the otolith, which can reveal when and where the fish spent time at different periods of its life. Closer examination of how these critical freshwater habitats are used by different life stages of perch, and how these food webs are interconnected spatially, is critical to conserving Great Lakes habitat quality and connectivity.

Photo credit: Michigan DNR

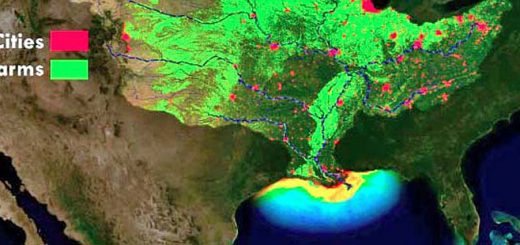

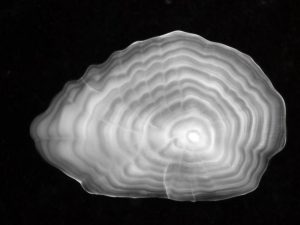

Otoliths resemble small white stones and are thought to support hearing, balance, and potentially navigation. They are comprised primarily of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), and grow throughout a fish’s life, adding new layers on a daily basis. Depending on environmental conditions, the Calcium component can be replaced by other trace elements, such as Strontium or Barium. For their study, the scientists compared the proportion of these trace elements in Yellow Perch otoliths each year of their life to the concentration of these elements at 12 coastal wetlands and near shore sites in Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. They were interested in habitat use by Yellow Perch and possible variation in life history strategies.

Otolith, photo credit: NOAA

The study found that Yellow Perch had three distinct life history patterns that were not previously documented. The first and most abundant group used wetland habitat once each year, likely during spawning in the spring. The second group was found to move between wetland and near shore habitats, up to twice per year. These movements may have occurred for foraging in nutrient rich wetlands, and to seek refuge from predators. The third group frequented wetland habitats for the first three years of life, but remained in near shore habitat afterwards. Small spikes in trace element concentrations were observed between otolith layers as well, which might indicate all perch could be making short-term visits to coastal wetlands.

A study site, Wildfowl Bay, MI. Photo credit: City of Caseville

A study site, Wildfowl Bay, MI. Photo credit: City of Caseville