Comparing habitat preference of aquatic life between beaches and riprap in Delaware Bay

Due to sea level rise and increased development in coastal areas, shoreline armoring has become an increasingly popular strategy to protect coastal communities and infrastructure. These armoring structures include seawalls, offshore breakwaters, bulkheads and riprap. Riprap is loose rock of various sizes that is piled up along the shoreline. While hardened shorelines are intended to provide structural protection, they have also been found to alter aquatic habitat by disrupting the natural movement of sediment. Unlike natural shorelines such as beaches and marshes that absorb wave energy, hardened shorelines reflect wave energy (Figure 1). This reflected energy erodes the sediment at the base of the structure and deepens the water along the shoreline.

Figure 1. Sand beach (left) and a riprap-hardened shoreline (right). Note the green algae on the rocks in the intertidal zone (from Torre and Targett 2016).

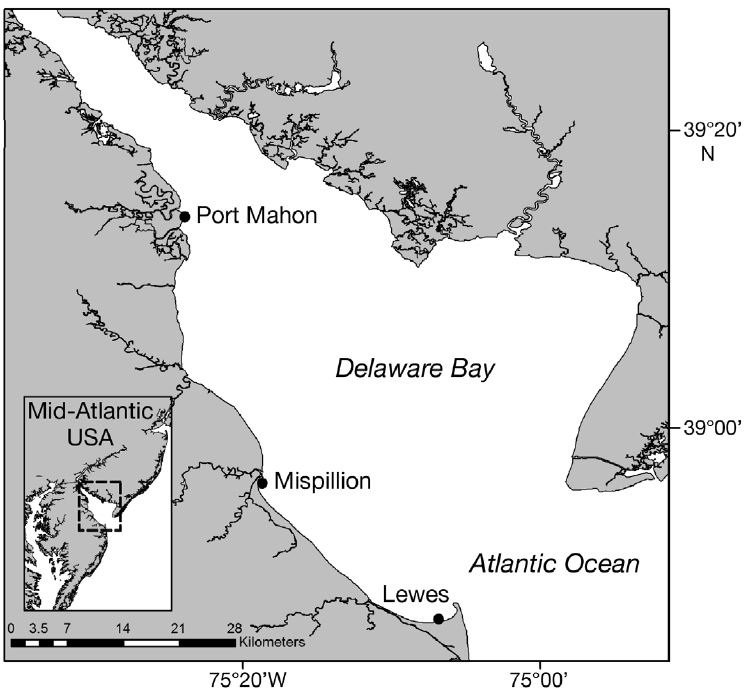

During the summers of 2012 and 2013, Michael Torre and Dr. Tim Targett from the University of Delaware examined the differences in the species composition and density of nekton (free-swimming organisms such as fish and crabs) between sand beaches and shorelines hardened with riprap. They chose three sites along the Delaware side of the bay in Lewes, Mispillion, and Port Mahon where sand beaches were adjacent to riprap shorelines (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Locations of the three sampling sites along the Delaware Bay. The salinity was highest at Lewes near the mouth of the bay (from Torre and Targett 2016).

Each site was sampled using a 36 meter bag-seine net with two hauls along the beach and two hauls along the riprap. For the seine-hauls along the riprap, a PVC pipe was thrust between the rocks to flush out the organisms in the crevices before the net was pulled in. They also added night sampling at the Lewes site in 2013 to monitor differences in the species present along the beach and riprap between day and night.

At Lewes and Mispillion, they collected a higher number of organisms along the sand beach than the riprap, and the fish and crab assemblages were distinctively different between the two shoreline habitats. Several species showed a preference for the sand beach habitat, including Atlantic silversides (Menidia menidia), spot (Leiostomus xanthurus), northern kingfish (Menticirrhus saxatilis) and Florida pompano (Trachinotus carolinus). The only species to show preference for riprap shorelines was the bay anchovy (Anchoa mitchilli). Because of the deeper water found along hardened shorelines, larger species of predatory fish are able to access the shore zone. Gently sloping sand beaches may provide a shallow water refuge for smaller fish.

At Port Mahon, the shoreline was primarily riprap (~95%) with a small stretch of sand beach. Because of its small size and the predominance of riprap around it, the beach may not have been able support its own distinct assemblage of fish and crabs. Differences were also found in the nekton assemblages between day and night. Bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix), a voracious predatory species, were more abundant during the day. Bay anchovies, spot, blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) and weakfish (Cynoscion regalis) were more dense at night. The preference of a particular species for beach or riprap was found to be consistent between day and night.

Compared with sand beaches, this study showed that riprap-hardened shorelines have different species assemblages and lower densities of fish and crabs. As shoreline armoring is becoming increasingly popular and widespread, it is important to understand how these structures alter aquatic habitat along the shoreline. Current research is being done on new shoreline stabilization techniques called “living shorelines”. These projects use natural materials, including native plants and oyster reefs, to reduce erosion and enhance habitat for fish and wildlife.

Reference:

Torre, M.P., and T.E. Targett. 2016. Nekton assemblages along riprap-altered shorelines in Delaware Bay, USA: Comparisons with adjacent beach. Marine Ecology Progress Series 548: 209-218.