Artificial Fisheries: Reservoirs and Smallmouth Bass

Reservoirs are artificial lakes that are created when humans dam rivers for irrigation, flood control, or hydroelectric power. Native fish species that take up residence in reservoirs may struggle to adapt because their new home is managed according to the rhythms of human activity and demand rather than natural flow regimes. A few challenges include the introduction of non-native species, habitat erosion, dramatic fluctuations in water depth, and shifting thermal regimes. In contrast, nonnative predators often flourish due to the concentrated abundance of forage fish. Forage fish often thrive in reservoirs because of multiple nutrient inputs from the dammed river or other inputs being deposited into the reservoir, providing phyto- and zooplankton for forage species and plentiful spawning habitat. Therefore, booms of forage fish populations like shad (Dorosoma spp.; Figure 1) and cisco (Coregonus spp.; Figure 2) are common. Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieu; Figure 3) are a species uniquely adapted for reservoir environments.

Figure 3. Smallmouth Bass caught from a Lac Seul, a reservoir in northwest Ontario. Credit: A. Vaisvil

Figure 1. Threadfin Shad (Dorosoma petense). Credit: A. Vaisvil

Figure 2. Cisco (Lake Herring) (Coregonus artedii). Credit: US Fish & Wildlife Service

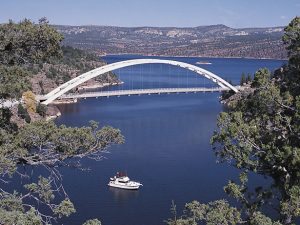

Habitat flexibility when foraging and during reproduction allow Smallmouth Bass to thrive in changes caused by reservoir fluctuations and habitat degradation (Hubert and Lackey 1980). Although not native to all reservoirs across the contiguous United States, these generalist predators thrive in the forage-rich waters of reservoirs where they excel at catching prey because of changes to habitat characteristics such as decreased turbidity (i.e., waters become clearer; Carter et al. 2009). Smallmouth bass adapt to waters inhabited by both warmwater and coldwater prey species because of their relatively large thermal tolerances, and can do well in areas where they are introduced or where waters have changed in areas where they are native. As long as summer water temperatures stay within a range for juvenile fish to grow (~59-90 ºF), Smallmouth Bass can thrive in reservoirs (Horning II and Pearson 1973). For example, Smallmouth Bass thrive in the Flaming Gorge Reservoir (Figure 4)where there is a coldwater trout fishery in northeastern Utah, as well as the Pickwick Reservoir (Figure 5), a warmwater reservoir supporting Catfish and Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides) in northern Alabama.Smallmouth Bass, as generalist predators that feed on aquatic insects, crayfish or other fish, consume any of the available forage. In addition, these fish are known for aggressively taking artificial lures/flies and for acrobatics once hooked. The excitement created by fishing for Smallmouth Bass has created a major demand to catch these fish throughout the United States and southern Canada. Annual fishing expenditures are approximately $45 billion annually with bass fishing making up $16 billion (Southwick Associates 2011). Although there are nine species of bass that are included in this fishery, Smallmouth Bass make up many of these fishing opportunities in reservoirs across the contiguous United States.

Figure 4. Flaming Gorge Reservoir in northern Utah along the Green River provides excellent fishing for Smallmouth Bass and Lake Trout (Salvelinus namaycush). Credit: US Bureau of Reclamation

Figure 5. Pickwick Lake, part of the Tennessee River, in northern Alabama is known for great Smallmouth Bass Fishing. Credit: Tennessee Valley Authority

Smallmouth Bass are well adapted for reservoir environments that typically put a strain on many native species. However, with the popularity of bass fishing and excitement of catching Smallmouth Bass, these fish make a stimulating opportunity for managers of reservoirs for recreation. Dams and reservoirs typically exist in an artificial environment that often create cultural, political and societal issues. When rivers are dammed, Smallmouth Bass are sometimes the best way to make the most of reservoir ecosystems.

References

Hubert, W.A. and Lackey, R.T. 1980. Habitat of adult smallmouth bass in a Tennessee River reservoir. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 109(4):364-370.

Horning II, W.B. and Pearson, R.E. 1973. Growth temperature requirements and lower lethal temperatures for juvenile smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieui). Journal of the Fisheries Board of Canada 30(8):1226-1230.

Carter, M.W., Shoup, D.E., Dettmers, J.M. and Wahl, D.H. 2010. Effects of turbidity and cover on prey selectivity of adult smallmouth bass. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 139(2):353-361.

Southwick Associates. 2011. Southwick bass fishing report. Report, Fernandina Beach, Florida.